Coke sustains itself with green consumers

Coca-Cola has invested in ambitious initiatives to make its

packaging more sustainable. Will the payback be there?

By Pan Demetrakakes, Editor

Are Coca-Cola’s sustainability efforts...sustainable?

Sustainability is more than a buzzword at the world’s largest non-alcohol beverage company. The Coca-Cola Co. has embarked on some of the most ambitious, and capital-intensive, initiatives to promote packaging sustainability of any major consumer goods corporation:

• Recycling goals that include 25% recycled content in all bottles and 100% recovery of all packaging by 2015.

• The world’s largest bottle-to-bottle recycling plant in Spartanburg, S.C., operated as a joint venture with a recycling company. This facility will allow the recycling of nearly 2 billion 20-ounce plastic bottles a year.

• The PlantBottle, 30% of which is made of a polymer derived from sugarcane. Introduced last year in Denmark and in December in western Canada, the PlantBottle is scheduled to roll out later this year in the northwestern U.S., as well as elsewhere in the world, for both water and carbonated beverages.

• A $400,000 grant last year to Michigan State University, home to one of the nation’s top packaging study programs, to establish a Center for Packaging Innovation and Sustainability.

• A packaging collection program that puts bottle-shaped recycling bins, most of them branded, in public places. More than 5,000 such bins have been distributed so far.

These efforts clearly go beyond “greenwashing,” the disparaging term for paying lip service to environmental concerns. Coca-Cola has made big promises on sustainability-and, especially with the Spartanburg plant and the PlantBottle, committed a lot of money to back them up.

“Coke’s been around for over a hundred years; we plan to be around for another hundred,” says Scott Vitters, Coca-Cola’s global director of packaging sustainability. “For sustainability, we’re making investments, whether it’s the PlantBottle or recycled-content technologies, that may have an incremental cost today, although we have worked very hard to have strategies on both that are focused on cost parity or better.”

The recycling plant in Spartanburg is arguably Coke’s most ambitious, high-profile sustainability effort to date. Coca-Cola has invested about $60 million in the plant, under the auspices of New United Resource Recovery Corp., a joint venture of which it owns 49%, and will be the customer for 60% of the recycled polyethylene terephthalate (PET) produced there.

Closed-loop, bottle-to-bottle recycling overcomes one of the biggest objections to package recycling as an environmental strategy, which is that most of the recycled resin can only be used for textiles or other non-packaging applications. That sort of recycling does nothing to address one of the central concerns about the use of plastic in bottles or other packaging: its contribution to the ongoing use, and depletion, of the world’s petroleum supply. But closed-loop recycling is expensive, mostly because of the costs of purifying recycled resin for beverage-contact applications.

Coke’s investment in the South Carolina recycling plant is perhaps the most obvious example of Coca-Cola using its size to accomplish sustainability goals that smaller companies can’t. A venture like the South Carolina plant is out of reach for all but the very biggest players.

“The simple fact of [Coca-Cola’s] size allows it to do things other companies couldn’t do,” says Andrew Dent, vice president of materials research for Material ConneXion, a consulting firm specializing in industrial materials.

No matter how big Coca-Cola is, however, it can’t ignore the laws of the marketplace. The most significant one in plastics is the price of oil, which drives the price of virgin resin.

“The advantage for recyclers, and ultimately for Coke, has all to do with [the price of] oil,” Dent says. “If suddenly polyester goes up in price because oil is more expensive, then recycled polyester becomes a viable source.”

Vitters agrees: “What is the price of petrochemicals? That is probably the biggest wild card when we talk about the price of recycled content or we talk about the PlantBottle.”

Recycled PET (rPET) prices are subject to other factors. “What is the cost of baled empty bottles? That cost often gets overlooked when we talk about this issue,” Vitters says.

However, the investment in the South Carolina recycling plant gives the company potential advantages no matter what happens in the market for rPET. If rPET prices plunge, the 25% recycled-content goal becomes easier to attain, at least economically. If they rise, Coke not only has a secure supply, but will share in the profits as its partner in the joint venture, United Resource Recovery Corp., gets more money for the rPET it sells on the open market.

Coca-Cola’s current rate of recycled material usage in the U.S. ranges from 10% to 25%, Vitters says. The differences are largely regional: Bottles distributed on the East Coast currently have higher recycled content. This is due to regional variations in the price of rPET. It’s more expensive on the West Coast because demand is higher, due to the option of shipping rPET in freighters returning to Asia. (China’s recent decision to allow imports of whole used PET bottles, as opposed to rPET flake, probably will drive up the price of rPET in the West, at least in the short term.)

Keeping it local

The regional variation in rPET content is a good example of how Coca-Cola’s business model, combining national presence with local bottling, translates to packaging issues. This model keeps Coke from having to transport water long distances; it works similarly for recycled plastic.

“We produce bottles all over the country, so we could ship [recycled] material from the East Coast over to the West Coast, but obviously, from an environmental and economic standpoint, that’s not as efficient,” Vitters says.

This is why the goal of 25% rPET content is being met first in the East and will gradually move West. It also accounts for the reverse direction for the rollout of another major Coca-Cola sustainability initiative: the PlantBottle, introduced into Western Canada and the U.S. to coincide with the Winter Olympics and scheduled to make its way eastward.

The PlantBottle, used for both Dasani water and carbonated beverages, has 30% content from a renewable source: polymer derived from sugarcane and molasses. Most of this material comes from Brazil, where the manufacture of ethanol from sugar processing waste is highly developed.

The PlantBottle has a significant advantage as bio-based packaging goes: It’s fully recyclable. Polylactic acid (PLA), the most common currently commercialized bio-based material, could contaminate and ruin a batch of PET being recycled. But that’s not an issue with the PlantBottle.

“Coke is building the blocks of PET in a different way, using a different source” from PLA, says Kate Eagle, spokesperson for the National Association for PET Container Resources (NAPCOR). “What they end up with is a PET that is chemically equivalent to a petrochemical-based PET.”

The PlantBottle is more expensive than all-petroleum-derived PET bottles, Vitters says: “We’re taking the first step in this journey. The current supply chain model with PlantBottle [material] has not been optimized [to the extent] that the 30-year-old virgin PET chain is today. We are today paying a premium in terms of being able to produce PlantBottle, but we have a long-term objective to bring that cost down.”

Who’s the green target?

The Spartanburg plant and the PlantBottle are examples of Coke putting real money behind sustainability initiatives. But is it all worth it? Whom is Coca-Cola targeting with these green initiatives? Is burnishing the corporate image this way going to sell more product, or at least mute the criticism that Coca-Cola gets on environmental grounds? And what obstacles will the company face in pursuit of its green goals?

Joel Makower, a consultant on corporate green issues and executive editor of GreenBiz.com, says Coca-Cola’s environmental initiatives make good business sense.

“Coke is a global brand, and like a number of global brands, Coke has taken a number of initiatives that have put it in a leadership position,” Makower says. “And like a number of other global brands, they didn’t necessarily come to this willingly, but once they began to embrace an environmental ethic, they realized that there was a wide range of unexplored opportunities that were not only good for the brand, but good for the bottom line.”

Bob Messenger, editor of The Morning Cup food and beverage industry newsletter, is a self-proclaimed skeptic about environmental efforts but wrote glowingly about Coke’s efforts in his March 11 edition: “Aggressively joining the movement to help save the planet will give Coke worldwide kudos (and soda-swigging loyalty) from tens of millions of people genuinely concerned about the state of the planet they live on.”

The emphasis on recycling makes sense when it’s seen as part of Coca-Cola’s concern for its package. To a degree perhaps unprecedented among consumer goods companies, the Coke bottle is Coke’s corporate image.

“The single most important thing Coke owns, their franchise, is their bottle,” says Bob Lilienfeld, a consultant and editor of the Use Less Stuff newsletter. “They will do whatever they have to do to burnish the reputation of that bottle. A hundred years ago, it meant putting that bottle in glass. Thirty years ago, it meant putting that bottle in PET. If tomorrow it means putting that bottle in a biopolymer package, they will do it, because their package represents the embodiment of what it is they need people to perceive about them.”

If the bottle is Coke’s image, that image took a beating during the years that Coke moved from returnable glass to disposable PET. The bottle was seen as trash-literally.

“For many years, when they came out with plastic bottles, that was a dent to its brand, because we see those plastic bottles everywhere,” Dent says. Because only about 27% of PET bottles in the U.S. are recycled, according to NAPCOR, that means the rest “are somewhere else-landfilled, out in the sea, on our sidewalks...so it’s an identifiable brand,” Dent says. “People will see a [discarded] Coke bottle somewhere, and that’s a bad thing.”

It’s especially bad when a negative image like a crushed, dirty bottle is associated with a huge corporation that’s the leader in a major industry segment. This is due to what Makower calls “the tyranny of brand leadership, where companies like Coca-Cola, McDonald’s and Nike will always be subject to higher scrutiny than their lower-ranked competitors.”

Corporate image efforts, for sustainability or anything else, will always be met with a certain amount of skepticism, especially by zealots-and the green movement has more than its share of those.

“There is a certain vocal part of activist world, bolstered by the Internet and the blogosphere, that are very quick to make charges of greenwash for any company that announces an environmental initiative that is seen as less than perfect,” Makower says. “Which is pretty much every corporate environmental initiative, by virtue of the fact that companies will never be perfect.”

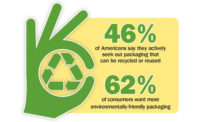

What complicates the picture is that when it comes to environmental initiatives, the public often talks a better game than it plays.

“A lot of companies have rushed to put their products in quote-unquote ‘environmentally friendly’ packaging, only to find out that consumers really don’t care,” Lilienfeld says. “Or if they do care, it’s still [more] about price and value and functionality.”

Makower echoes that view, claiming that consumers show “a certain amount of hypocrisy” on environmental products. “For more than 20 years, market research polls have shown consumers saying overwhelmingly that they want to buy green products from quote-unquote ‘good companies,’” he says. “But they also say that they don’t trust companies when companies make green claims.”

Coca-Cola, however, must be doing something right. They were named in both Forbes and Fortune this year (among others) as one of the 10 most admired U.S. companies, with its environmental initiatives playing a big role. Company officials are confident that this kind of connection with consumers will develop and spread.

“I think general consumers are getting increasingly interested in knowing the environmental performance and commitment as companies,” Vitters says. “Instead of viewing that as a threat or risk, we’re really excited about viewing that as an opportunity for our business.” F&BP

PlantBottles for Coca-Cola and Dasani are being rolled out in selected markets.

By Pan Demetrakakes, Editor

Are Coca-Cola’s sustainability efforts...sustainable?

Sustainability is more than a buzzword at the world’s largest non-alcohol beverage company. The Coca-Cola Co. has embarked on some of the most ambitious, and capital-intensive, initiatives to promote packaging sustainability of any major consumer goods corporation:

• Recycling goals that include 25% recycled content in all bottles and 100% recovery of all packaging by 2015.

• The world’s largest bottle-to-bottle recycling plant in Spartanburg, S.C., operated as a joint venture with a recycling company. This facility will allow the recycling of nearly 2 billion 20-ounce plastic bottles a year.

• The PlantBottle, 30% of which is made of a polymer derived from sugarcane. Introduced last year in Denmark and in December in western Canada, the PlantBottle is scheduled to roll out later this year in the northwestern U.S., as well as elsewhere in the world, for both water and carbonated beverages.

• A $400,000 grant last year to Michigan State University, home to one of the nation’s top packaging study programs, to establish a Center for Packaging Innovation and Sustainability.

• A packaging collection program that puts bottle-shaped recycling bins, most of them branded, in public places. More than 5,000 such bins have been distributed so far.

These efforts clearly go beyond “greenwashing,” the disparaging term for paying lip service to environmental concerns. Coca-Cola has made big promises on sustainability-and, especially with the Spartanburg plant and the PlantBottle, committed a lot of money to back them up.

“Coke’s been around for over a hundred years; we plan to be around for another hundred,” says Scott Vitters, Coca-Cola’s global director of packaging sustainability. “For sustainability, we’re making investments, whether it’s the PlantBottle or recycled-content technologies, that may have an incremental cost today, although we have worked very hard to have strategies on both that are focused on cost parity or better.”

Branded recycling bins are a way for Coca-Cola to remind consumers of its sustainability initiatives.

Closing the loop

The recycling plant in Spartanburg is arguably Coke’s most ambitious, high-profile sustainability effort to date. Coca-Cola has invested about $60 million in the plant, under the auspices of New United Resource Recovery Corp., a joint venture of which it owns 49%, and will be the customer for 60% of the recycled polyethylene terephthalate (PET) produced there.

Closed-loop, bottle-to-bottle recycling overcomes one of the biggest objections to package recycling as an environmental strategy, which is that most of the recycled resin can only be used for textiles or other non-packaging applications. That sort of recycling does nothing to address one of the central concerns about the use of plastic in bottles or other packaging: its contribution to the ongoing use, and depletion, of the world’s petroleum supply. But closed-loop recycling is expensive, mostly because of the costs of purifying recycled resin for beverage-contact applications.

Coke’s investment in the South Carolina recycling plant is perhaps the most obvious example of Coca-Cola using its size to accomplish sustainability goals that smaller companies can’t. A venture like the South Carolina plant is out of reach for all but the very biggest players.

“The simple fact of [Coca-Cola’s] size allows it to do things other companies couldn’t do,” says Andrew Dent, vice president of materials research for Material ConneXion, a consulting firm specializing in industrial materials.

Labeling for the PlantBottle spells out its environmental benefits to consumers.

Supply and demand

No matter how big Coca-Cola is, however, it can’t ignore the laws of the marketplace. The most significant one in plastics is the price of oil, which drives the price of virgin resin.

“The advantage for recyclers, and ultimately for Coke, has all to do with [the price of] oil,” Dent says. “If suddenly polyester goes up in price because oil is more expensive, then recycled polyester becomes a viable source.”

Vitters agrees: “What is the price of petrochemicals? That is probably the biggest wild card when we talk about the price of recycled content or we talk about the PlantBottle.”

Recycled PET (rPET) prices are subject to other factors. “What is the cost of baled empty bottles? That cost often gets overlooked when we talk about this issue,” Vitters says.

However, the investment in the South Carolina recycling plant gives the company potential advantages no matter what happens in the market for rPET. If rPET prices plunge, the 25% recycled-content goal becomes easier to attain, at least economically. If they rise, Coke not only has a secure supply, but will share in the profits as its partner in the joint venture, United Resource Recovery Corp., gets more money for the rPET it sells on the open market.

Coca-Cola’s current rate of recycled material usage in the U.S. ranges from 10% to 25%, Vitters says. The differences are largely regional: Bottles distributed on the East Coast currently have higher recycled content. This is due to regional variations in the price of rPET. It’s more expensive on the West Coast because demand is higher, due to the option of shipping rPET in freighters returning to Asia. (China’s recent decision to allow imports of whole used PET bottles, as opposed to rPET flake, probably will drive up the price of rPET in the West, at least in the short term.)

Keeping it local

The regional variation in rPET content is a good example of how Coca-Cola’s business model, combining national presence with local bottling, translates to packaging issues. This model keeps Coke from having to transport water long distances; it works similarly for recycled plastic.

“We produce bottles all over the country, so we could ship [recycled] material from the East Coast over to the West Coast, but obviously, from an environmental and economic standpoint, that’s not as efficient,” Vitters says.

This is why the goal of 25% rPET content is being met first in the East and will gradually move West. It also accounts for the reverse direction for the rollout of another major Coca-Cola sustainability initiative: the PlantBottle, introduced into Western Canada and the U.S. to coincide with the Winter Olympics and scheduled to make its way eastward.

The PlantBottle, used for both Dasani water and carbonated beverages, has 30% content from a renewable source: polymer derived from sugarcane and molasses. Most of this material comes from Brazil, where the manufacture of ethanol from sugar processing waste is highly developed.

The PlantBottle has a significant advantage as bio-based packaging goes: It’s fully recyclable. Polylactic acid (PLA), the most common currently commercialized bio-based material, could contaminate and ruin a batch of PET being recycled. But that’s not an issue with the PlantBottle.

“Coke is building the blocks of PET in a different way, using a different source” from PLA, says Kate Eagle, spokesperson for the National Association for PET Container Resources (NAPCOR). “What they end up with is a PET that is chemically equivalent to a petrochemical-based PET.”

The PlantBottle is more expensive than all-petroleum-derived PET bottles, Vitters says: “We’re taking the first step in this journey. The current supply chain model with PlantBottle [material] has not been optimized [to the extent] that the 30-year-old virgin PET chain is today. We are today paying a premium in terms of being able to produce PlantBottle, but we have a long-term objective to bring that cost down.”

Who’s the green target?

The Spartanburg plant and the PlantBottle are examples of Coke putting real money behind sustainability initiatives. But is it all worth it? Whom is Coca-Cola targeting with these green initiatives? Is burnishing the corporate image this way going to sell more product, or at least mute the criticism that Coca-Cola gets on environmental grounds? And what obstacles will the company face in pursuit of its green goals?

Joel Makower, a consultant on corporate green issues and executive editor of GreenBiz.com, says Coca-Cola’s environmental initiatives make good business sense.

“Coke is a global brand, and like a number of global brands, Coke has taken a number of initiatives that have put it in a leadership position,” Makower says. “And like a number of other global brands, they didn’t necessarily come to this willingly, but once they began to embrace an environmental ethic, they realized that there was a wide range of unexplored opportunities that were not only good for the brand, but good for the bottom line.”

Bob Messenger, editor of The Morning Cup food and beverage industry newsletter, is a self-proclaimed skeptic about environmental efforts but wrote glowingly about Coke’s efforts in his March 11 edition: “Aggressively joining the movement to help save the planet will give Coke worldwide kudos (and soda-swigging loyalty) from tens of millions of people genuinely concerned about the state of the planet they live on.”

The emphasis on recycling makes sense when it’s seen as part of Coca-Cola’s concern for its package. To a degree perhaps unprecedented among consumer goods companies, the Coke bottle is Coke’s corporate image.

“The single most important thing Coke owns, their franchise, is their bottle,” says Bob Lilienfeld, a consultant and editor of the Use Less Stuff newsletter. “They will do whatever they have to do to burnish the reputation of that bottle. A hundred years ago, it meant putting that bottle in glass. Thirty years ago, it meant putting that bottle in PET. If tomorrow it means putting that bottle in a biopolymer package, they will do it, because their package represents the embodiment of what it is they need people to perceive about them.”

If the bottle is Coke’s image, that image took a beating during the years that Coke moved from returnable glass to disposable PET. The bottle was seen as trash-literally.

“For many years, when they came out with plastic bottles, that was a dent to its brand, because we see those plastic bottles everywhere,” Dent says. Because only about 27% of PET bottles in the U.S. are recycled, according to NAPCOR, that means the rest “are somewhere else-landfilled, out in the sea, on our sidewalks...so it’s an identifiable brand,” Dent says. “People will see a [discarded] Coke bottle somewhere, and that’s a bad thing.”

It’s especially bad when a negative image like a crushed, dirty bottle is associated with a huge corporation that’s the leader in a major industry segment. This is due to what Makower calls “the tyranny of brand leadership, where companies like Coca-Cola, McDonald’s and Nike will always be subject to higher scrutiny than their lower-ranked competitors.”

Corporate image efforts, for sustainability or anything else, will always be met with a certain amount of skepticism, especially by zealots-and the green movement has more than its share of those.

“There is a certain vocal part of activist world, bolstered by the Internet and the blogosphere, that are very quick to make charges of greenwash for any company that announces an environmental initiative that is seen as less than perfect,” Makower says. “Which is pretty much every corporate environmental initiative, by virtue of the fact that companies will never be perfect.”

What complicates the picture is that when it comes to environmental initiatives, the public often talks a better game than it plays.

“A lot of companies have rushed to put their products in quote-unquote ‘environmentally friendly’ packaging, only to find out that consumers really don’t care,” Lilienfeld says. “Or if they do care, it’s still [more] about price and value and functionality.”

Makower echoes that view, claiming that consumers show “a certain amount of hypocrisy” on environmental products. “For more than 20 years, market research polls have shown consumers saying overwhelmingly that they want to buy green products from quote-unquote ‘good companies,’” he says. “But they also say that they don’t trust companies when companies make green claims.”

Coca-Cola, however, must be doing something right. They were named in both Forbes and Fortune this year (among others) as one of the 10 most admired U.S. companies, with its environmental initiatives playing a big role. Company officials are confident that this kind of connection with consumers will develop and spread.

“I think general consumers are getting increasingly interested in knowing the environmental performance and commitment as companies,” Vitters says. “Instead of viewing that as a threat or risk, we’re really excited about viewing that as an opportunity for our business.” F&BP

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!