Cover Story: Regulations

OSHA Regulations Affecting the Printing Ink, Graphic Arts and Flexible Packaging Industries

OSHA Hot Topics

OSHA has been very vocal about several projects in 2013:

- Workplace Violence: OSHA introduced a new program focusing on the prevention of violence in the workplace, urging employers to examine their emergency action plans and plan for contingencies such as violent ex-spouses of employees or ex-employees showing up at the workplace.

- Expansion of OSHA’s Whistleblower Program: OSHA recently unveiled a new whistleblower website, www.whistleblowers.gov, to encourage employee reporting of retaliation claims.

- Recordkeeping Emphasis: OSHA presumes many employers are habitually not recording workplace injuries, and have directed its inspectors to inspect and scrutinize employers’ OSHA 300 logs during inspections.

- Expanded Rulemaking Agenda: OSHA indicated in 2013 that it intends to aggressively publish new and updated OSHA regulations in administrative rulemaking, including publication of new rules to regulate combustible dust and require employers to create, implement and maintain written injury and illness prevention programs (called “I2P2” by OSHA). In late August, OSHA announced and published an updated silica exposure regulation, the first update to the standard in over 40 years.

OSHA Enforcement in the Printing Ink Industry

OSHA’s recent enforcement efforts have moderately targeted the printing ink industry. In calendar year 2012, OSHA conducted at least 38 inspections of employers classified under SIC 2893 (printing ink) and NAICS 325130 (synthetic dye and pigment manufacturing) and 325190 (printing ink manufacturing). Most OSHA inspections occurred in the eastern half of the country, in states such as Pennsylvania, Kentucky, North Carolina, Ohio and West Virginia. Only 14 of the 38 inspections occurred in states west of the Mississippi River, focused primarily on Missouri, California, Nevada, Minnesota and Louisiana.

OSHA issued employers citations in fifty percent of these inspections, with fines ranging from $1,125 to $25,000 per inspection. The agency most commonly cited PPE violations (8 times), followed by Lockout-Tagout (7 times), Powered Industrial Trucks (6 times), Respirators (5 times), Electrical (4 times), and Machine Guarding (4 times)

Hazard Communication Implementation of GHS

One of the main OSHA regulation updates significantly impacting the printing ink, graphic arts and flexible packaging industries has been OSHA’s update of the Hazard Communication (Hazcom) standard, located at 29 C.F.R. § 1910.1200. In 2010, OSHA published a final rule updating the Hazcom standard to implement the United Nations’ Globally Harmonized System (GHS) of classifying and labeling chemicals, with the first parts of the regulation to go into effect on December 1, 2013. The United Nations created the GHS due to concern that different label requirements in each country would impair the global chemical manufacturing industry and present a hazard to workers.

OSHA did not change the general structure of Hazard Communication. Chemical manufacturers and importers still classify hazards of their chemicals and convey that information to employers in the form of labels and safety data sheets; employers prepare a written hazcom program and convey that information to employees, along with training on the program elements. But OSHA did change how the information is passed along at each step of the process. OSHA also changed the regulation from a performance-based standard (convey the information in a way you think works best) to a specification standard (here’s how you will convey the information).

|

Hazard Communication Standard (HCS) |

|

Changes You Need to Know

OSHA added, removed and rewrote many definitions in the HazCom standard to align it with GHS terminology. The agency also did away with the “one study rule” and eliminated the “floor” of chemicals considered hazardous. There is no longer any such “floor,” and companies can no longer rely on one study in determining how to classify their chemicals. Instead, they must classify chemicals based on the “full range of available scientific literature and other evidence concerning the potential hazards.” OSHA did emphasize that the new standard does not require testing of chemicals to determine their hazards.

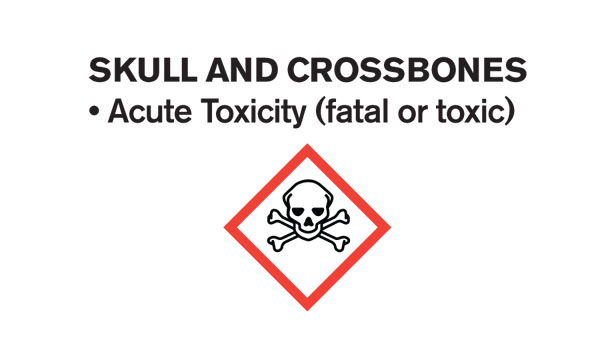

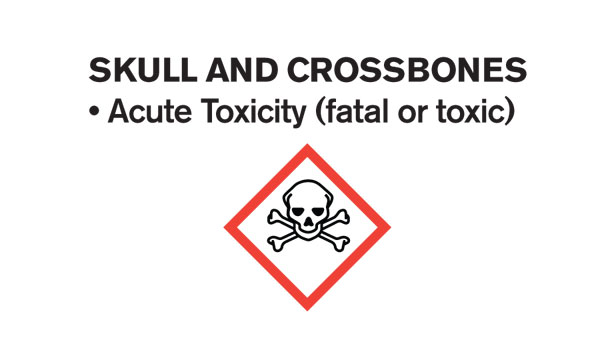

The updated HazCom standard now has a set and finite number of health and physical hazard classes, and each hazard class has one or more degrees of severity. (Hazards not on the lists become “Hazards Not Otherwise Classified.”) It is important to note that GHS labels its most severe hazards with “1” or “1A,” unlike the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) diamond classification system under NFPA 704 or the American Coatings Association’s Hazardous Materials Identification System (HMIS) system, both of which reserve “4” for the most severe hazards. This change did not sit well with either group.

The new standard does not outlaw NFPA 704 or the HMIS system. Either may still be used in addition to the GHS. During rulemaking, however, the NFPA rightly pointed out that the inverted numbering systems may create confusion among workers about the severity of hazards. Workers in the United States, after all, are used to seeing a “4” for the most severe hazards; when they see 1s all over the new GHS labels, they may incorrectly assume the chemicals they are working with are mild. OSHA seemed sympathetic to the NFPA’s concern, but maintained that its hands were tied and insisted that they could not materially change the GHS.

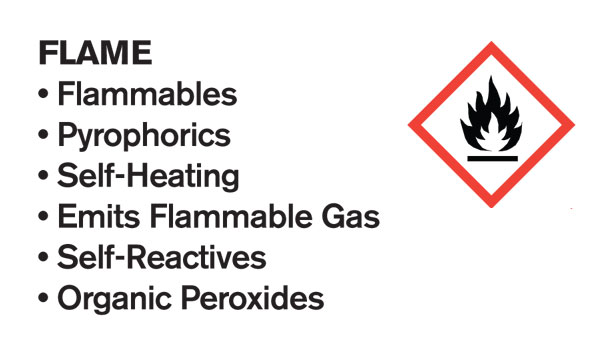

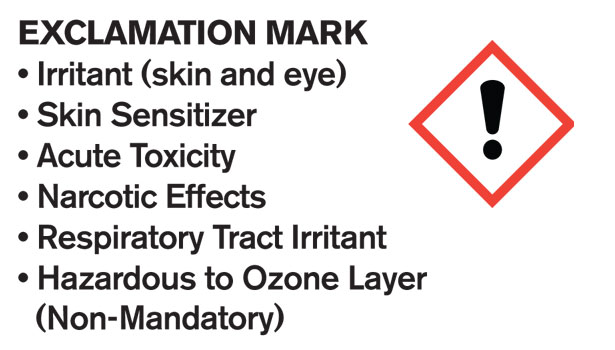

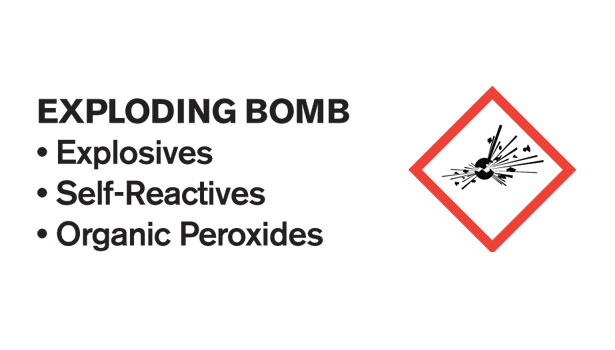

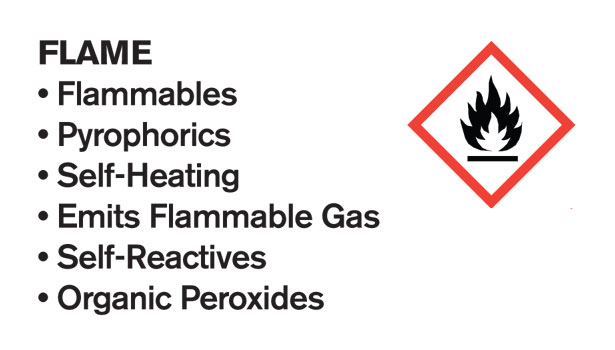

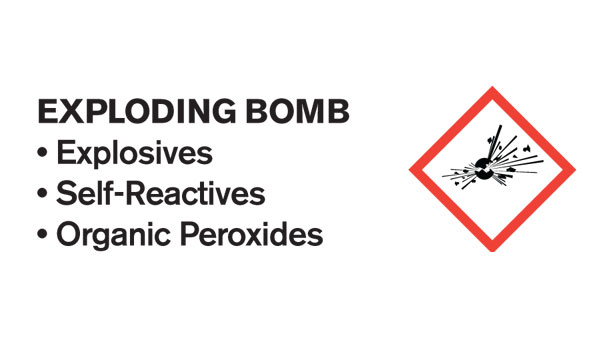

Labeling Requirements, No More MSDS

OSHA’s revised standard materially changed labeling requirements. The old 1994 standard left labeling specifics to chemical manufacturers and importers; just get the information on the label, in whatever way you think works best. The new standard requires shipped chemicals to be labeled with precise and specific information, namely product identifier, signal word, hazard statement(s), pictograms, precautionary statements and responsible party information. Nearly all discretion on what to say about a hazard and how to say it has been removed. Now, once companies have classified their particular chemical’s hazards, they must consult Appendix C to 1910.1200 (informally referred to as the “cookbook” by OSHA) for the precise language and pictograms to use on the labels. Appendix C is an approximately 60-page laundry list of sample labels, instructing companies on the exact wording of signal words, hazard statements, precautionary statements and pictograms to use for each class and category of hazard.

The revised standard also replaces Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) with Safety Data Sheets (SDS). The 1994 standard required that manufacturers convey all information about hazards in chemicals on an MSDS, but left it to them to determine the format and order of information. The new standard now has a lockstep 16-item SDS. Box 1 will always contain substance/mixture and supplier identification; Box 2 will always contain hazard identification; Box 3 will always contain composition/information on ingredients; Box 4 will always have first aid measures; and so forth. Appendix D to 1910.1200 contains the bare minimum information that must go in each box.

The first implementation date is coming up on December 1. By that deadline, all employers must train their employees on the new labels, label elements and the new SDS format. Full compliance with the new HazCom requirements goes into effect on June 1, 2015. To allow companies to deplete their non-compliant inventories, OSHA is allowing companies to continue to sell and ship containers with non-GHS labels until December 1, 2015.

Combustible Dust

Combustible dust was once thought to be a rare problem, largely confined to industries handling coal, sawdust, grain and wood. In 2006, however, the United States Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (CSB) released a study analyzing 275 incidents over a 25-year-period, resulting in over 1,000 workplace injuries. The CSB concluded that combustible dust could occur in a variety of industries, and called on OSHA to create a standard.

OSHA has started rulemaking on combustible dust, but no proposed rule has been released. The agency also has launched a combustible dust national emphasis program, focusing on reducing hazards.

With no specific standard to cite, OSHA relies on section 5(a)(1) of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 (OSH Act), more commonly known as the General Duty Clause. The General Duty Clause requires employers to furnish to each of their employees “employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm.” To establish a recognized hazard, OSHA typically relies upon NFPA 654, Standard for the Prevention of Fires and Dust Explosions from the Manufacturing, Processing, and Handling of Combustible Particulate Solids.

NFPA 654 contains many recommendations for mitigating combustible dust hazards. Its main three prongs are: (a) housekeeping; (b) fire prevention and protection; and (c) dust control. Ensure that dust accumulations and other combustibles are frequently cleaned up. Maintain alarms systems, emergency action plans and fire prevention plans. Ensure flammable materials are stored in appropriate locations. Utilize Lockout-Tagout procedures. Regularly inspect any areas where dust may accumulate. Maintain regular cleaning schedules with equipment specially approved for dust collection.

Recordkeeping

Finally, OSHA is scrutinizing employers’ OSHA 300 logs closer than ever. Many employers frequently make good faith mistakes on their logs. The recordkeeping rules themselves are not exactly models of clarity. Two areas that frequently trip up companies are determining when medical treatment beyond first aid is administered (triggering recording), and determining whether an incident is work-related.

“Medical treatment beyond first aid” is one of the final recordability triggers under 29 C.F.R. § 1904.4. Two key things to remember about the term is: (1) “medical treatment” is not everything you think it might include; and (2) OSHA’s definition of “first aid” can be idiosyncratic. Some items are common sense (Band-Aids); others are not (tetanus shots).

OSHA defines “medical treatment” under section 1904.7(b)(5)(i) as “management and care of a patient to combat disease or disorder.” The agency then carves out three critical exceptions to this definition. First, “visits to a physician or other licensed health care physician solely for observation or counseling” do not count. Second, diagnostic procedures, such as x-rays, blood tests and prescription medications for diagnostic purposes (think eye drops to dilate pupils) also do not count. Finally, “first aid” does not count.

So what exactly does OSHA call “first aid?” In essence, everything listed at 29 C.F.R. § 1904.7(b)(5)(ii): nonprescription medication (at nonprescription strength); tetanus shots; cleaning, flushing, or soaking surface skin wounds; bandages; hot/cold therapy; non-rigid means of support (back belts, wraps); temporary immobilization devices (splints, neck collars); drilling a fingernail or toenail to relieve pressure or drain fluid; eye patches; removing foreign objects from eyes with cotton swabs or irrigation; using splinters to remove foreign objects from anywhere else on your body but the eyes; finger guards; massages (but physical therapy and chiropractic messages count); and drinking fluids to relieve heat stress.

In other words: If it’s on OSHA’s list, it is considered first aid. If it is not on OSHA’s list, it’s not. Some other common misconceptions about OSHA’s recording rules include:

- Prescription medications. All prescription medications, no matter how benign, trigger recordability. Even an antibiotic prescribed solely as a preventative measure.

- Unfilled prescriptions. In OSHA’s eyes, once the doctor prescribes the medication, the visit goes beyond observation and counseling, regardless of whether the employee agrees or not. But in certain circumstances, an employer can send the employee to a another doctor for a second opinion on the need for medical treatment, and then decide which recommendation is the most authoritative and record the case based on that recommendation.

- Reductions. Popping a dislocated finger back into place, regardless of whether done by a physician or the employee himself, does not qualify as “first aid” and is recordable.

- Dentures and prosthetics. If an employee was, for example, struck by an object that damaged his dentures but nothing else (and would have smashed his original teeth if he had them), the incident would not be recordable. Damage to eye glasses, canes, and prosthetic arms or legs also are not recordable.

- Determining whether an injury is work-related can be even more difficult. OSHA broadly defines “work related” if an event or exposure in the work environment contributed to a resulting condition or significantly aggravated a pre-existing injury or illness. But OSHA has several quirky exceptions, all located within section 1904.5, including:

- An employee checking into a hotel on a business trip creates a “home away from home,” whereupon any injuries suffered in the room are not work related;

- But employees on a business trip perishing in a commercial airline disaster qualifies as a work-related injury, in spite of the fact the employer has no control over the airliner;

- An employee getting into an auto accident in the company parking lot is not work related, but an employee spraining her ankle in the parking lot on her way in is work related;

- Injuries at company-sponsored recreational events, like softball games, company picnics, etc., are not work-related, unless attendance is compulsory. In that case, tearing your ACL while throwing out the tying runner at the company softball game is a work-related injury.

- Self-inflicted injuries are not work related, but OSHA considers an employee breaking his hand after smashing it into a cabinet (upon hearing news of a layoff) to be recordable. The employee, OSHA reasoned, reacted without thought of injuring himself.

All of these hypotheticals come from OSHA’s own letters of interpretation and materials on the subject.

The industry must train workers in the new GHS HazCom labels and SDS by December 1. OSHA inspections after that date will routinely ask to inspect employers’ HazCom programs and to verify that GHS training occurred.

NAPIM

In August of this year, the National Association of Printing Ink Manufacturers (NAPIM) conducted a webinar covering federal health and safety regulations that have a direct impact on the printing ink manufacturing and related graphic communications industries. NAPIM wishes to express its sincere thanks and gratitude to John Martin of NAPIM’s legal counsel Ogletree Deakins for the expert guidance provided in the webinar.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!